Thanks for the (Soil) Memories

In my own work on pedology, soil geography, and soil geomorphology, there are at least three overlapping concepts of soil memory (or pedological memory) that at least generally, if clumsily, parallel the pedological literature as a whole.

One is based on the fundamental idea of soils as products of the environment, reflecting the combined, interacting influences of geological (or other) parent material, hydrological and geomorphological processes, climate, biota, all changing over time, and affecting each other and affected by the soil itself. This is the factorial or state factor model of soils going back to Dokuchaev and Jenny, and the conceptual basis of soil geography, surveying and mapping. Inverting the logic—soils as evidence of the environment rather than the environment as an explainer of soils—is the basis of paleopedology and paleoenvironmental interpretations of paleosols. This concept of soil memory is that soils “remember” the environmental factors influencing their genesis and development.

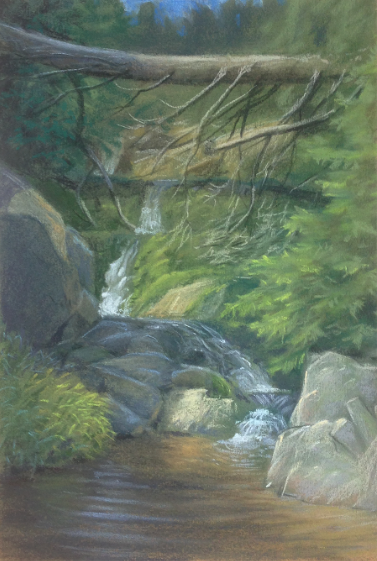

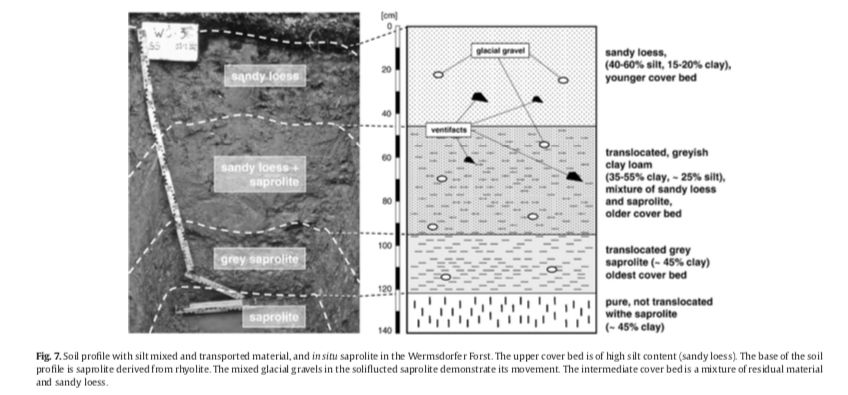

Carsten Lorz has used the memory of soils such as this one in Saxony, Germany, to reconstruct Quaternary pedogenesis.