Pictures of Landscape Evolution

A Czech mountain forest (Petr Mores)

Scientific communication is, in essence, storytelling. When our intended audience is restricted to other scientists of similar interests and expertise, we have both more and less freedom. More in the sense that a certain baseline knowledge base can be assumed—thus basic principles do not have to be reviewed, terms defined, and justifications made. While the language standards for rigor and precision are pretty strict, those for beauty and entertainment value are very low (though some voluntarily exceed these!). Less freedom in that there exist some pretty strict norms with respect to professionally and sociologically acceptable ways to communicate—if you want to get published, you’d better either adhere to these or give a damn compelling reason in those (rare) cases when you don’t. A couple of my recent posts linking storytelling to scientific norms in the geosciences, or attempting to: Earth science historical narrative plotlines, and an analysis of landscape evolutionary pathway stories.

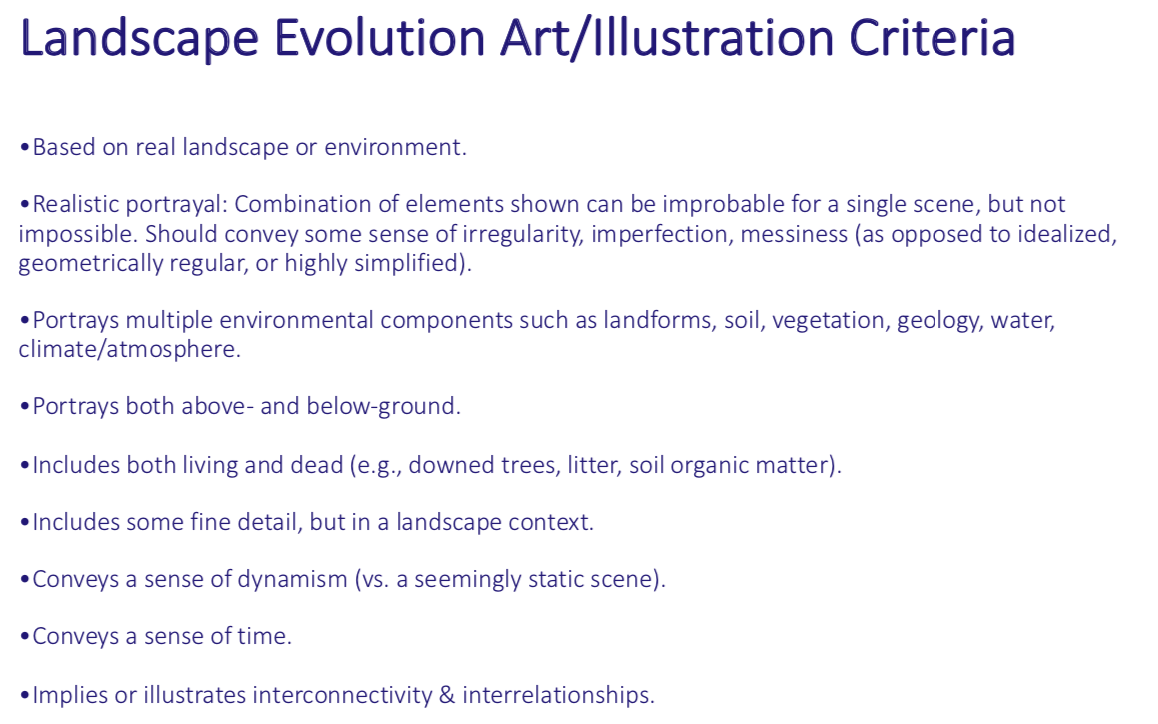

I’m doing a book on landscape evolution (in production now at Elsevier, so hopefully it won’t be too long), and therefore have been thinking about how to tell landscape evolution stories visually or graphically. Mostly I use photographs or box-and-arrow or flow chart type diagrams. The latter are a good, or at least honest and appropriate, approach for me, as my formal and mathematical analyses are often based on these. However, they have little aesthetic value, don’t help readers really visualize what is happening, and are intuitively appealing only to a small set of humans. And even the best photographs cannot always show everything you want to show—a simple example is that even the most wonderful photo of a forest, swamp, or wheat field cannot show the important stuff happening below ground. And even the best picture of an outcrop or soil profile can only represent a tiny portion of the surface.

Tree-rock interactions (Petr Mores)

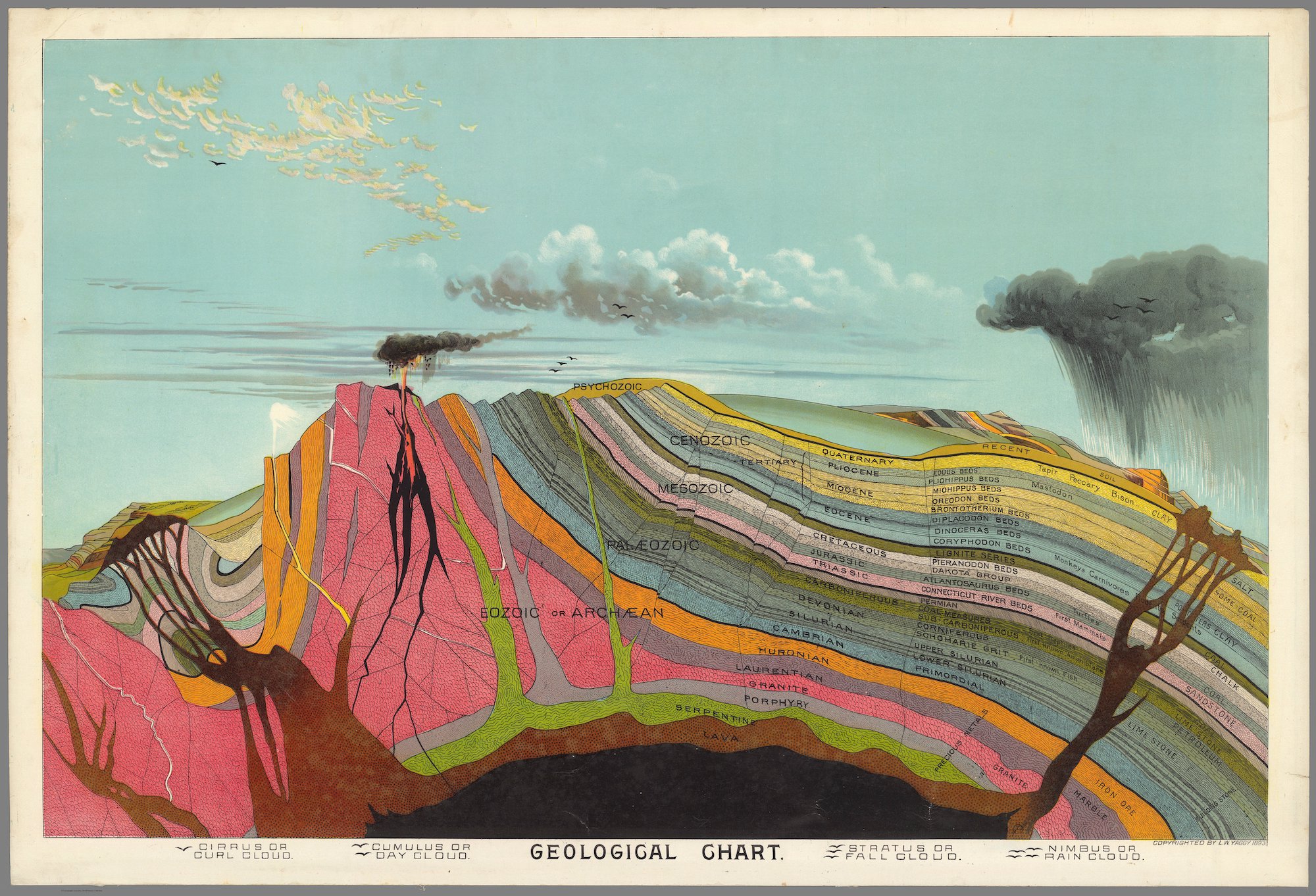

So, I started thinking in terms of art--not an original idea, by any means. There are a number of recent articles and projects on collaborations between scientists and artists, and a long tradition of scientist/artists and outstanding scientific illustrators. In the geosciences, I think of Walter Kubiena’s wonderful watercolors of soil profiles, Erwin Raisz’s landform maps, William Morris Davis’ landscape block diagrams, and Levi Walter Yaggy’s 1887 Geographical Portfolio.

Examples from Walter Kubiena’s Soils of Europe. So many people were cutting up copies of the manuscript to use the watercolor profiles as art, a separate addition with just the plates was published as Atlas of Soil Profiles (1954).

A plate from L.W. Yaggy’s Geographical Portfolio.

In 2018, while working with Pavel Šamonil in the Czech Republic, I met Pavel’s friend Petr Mores, a nature artist in Brno and a video game designer. Petr was working with Pavel on some illustrating some material for laypersons on the interactions among trees, rocks, soil, and landforms in Czech old-growth forests. I was immediately taken with Petr’s feel for the landscape, artistically and with respect to detail and accuracy. Last summer, as I was pondering these issues, I contacted Petr basically to pick his brain about the issues described above. Instead, that initial contact blossomed into an ongoing collaboration.

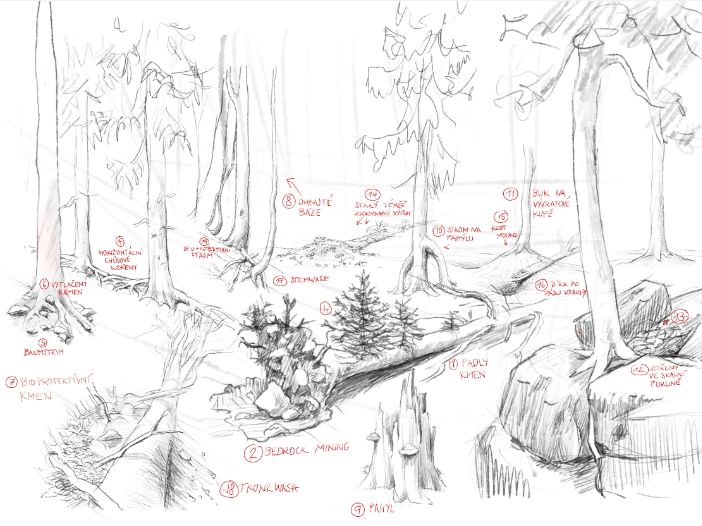

An annotated pencil sketch showing tree effects on soils, rocks, and landforms in Boubinsky Primeval Forest. This was an intermediate phase in a final piece Petr produced for Sumava magazine (in Czech).

An excerpt from my first e-mail to Petr: . . . I am working on a scientific monograph on landscape evolution, combining geomorphic, pedological, hydrological, and ecological aspects. Scientific communication is storytelling, and in telling my stories I find myself constrained in having to do so sequentially--if not chronologically then via a sequence of arguments and evidence or a layering on of different phenomena. But what I want to convey, at some point, is the idea that landscape evolution is not a linear or even nonlinear progression through time, or an additive sequence of steps or effects. Rather, it is a constantly changing totality, more a churning urn of burning funk than a layered construct (as you see, my metaphors are failing me here, and in person at this point I would have resorted to various hand motions and nonverbal actions). Because this is a scientific monograph published by a scientific publisher (Elsevier), I am mostly constrained by the conventions of scientific communication. But I want to include, if possible, something that more clearly conveys the idea of landscape evolution as a never-ending story, with constant (or at least chronic) interactions within it.

Do you think it is possible for a drawing or painting to convey this sort of feel? I recall, vaguely I must admit, getting that sense from some of your drawings (Pavel sent me the Sumava magazine piece, which is the only example I have in hand right now). But I am already wired to think and interpret things that way. Could the same effect be achieved for more typical scientists, who are not predisposed to see things that way?

And key points of Petr’s response: . . . . I might approach it from a slightly different angle, but perhaps a complementary one - what I lack in knowledge, I try to make up with not just observation but also contemplation of my intuition and emotional response.

To your question: I think something like you mention can be attempted for sure, especially if an artist and a scientist work together closely. I don't know how far I could get with my skills, but I would love to try, just like I did with Pavel! It was a very enjoyable experience for me to gather all of my field sketches and work out a composition that combines all of Pavel's checklist items into one improbable, but still theoretically possible image that attempts to show things that would never fit into a single photo.

From what you are writing, I imagine that this could be at least a starting point to what you're after - to show an overlap of more phenomena and processes, even from multiple viewpoints (overground/underground) to capture these processes not in isolation but as interconnected? Could that be close or am I completely misconstruing it?

I tend to work in different modes (small to big, slow to fast) and a few different media because I find that each method tends to reveal different aspects, perhaps tells a different story (or different part of it), depending what I'm trying to do at the moment or what the assignment is. The handful of images below show some of the range, from details to the whole, from emphasis on color/mood to shapes/description etc. So I try to be flexible and do what's needed instead of just constraining myself within a particular style.

If I can afford it, one particularly interesting but very time-consuming method is to work in a single place repeatedly, using different media and approaches. Each study then reveals a different aspect of the place, its story and its spirit, which can be later overlaid, as it were, to create an image that tells more about the landscape than any single insight could. It is like laborious mining for the true soul of the place, to use my own imperfect metaphor - you only get one fragment of the puzzle at a time, then the fun is to try to connect them and make sense of them all! . . .

Challenge answered! My next step was to try to come up with some ideal critieria:

And off we went! As best we could, anyway—Petr (and Pavel, who is also closely involved) have full time day jobs, and so did I for the first six months of this. Not to mention families, pandemics, etc.

I will tell more of the story in future posts.

Questions or comments: jdp@uky.edu

Contact the artist: petr.mores@uh.cz

Posted 28 January 2021