THE ART OF SCIENTIFIC STORYTELLING (PART 3)

This installment continues the story of my collaboration (along with fellow scientist Pavel Šamonil) with Czech artist Petr Mores in combining visual art and science to tell the story of landscape evolution of forests, topography, and soils in the Šumava Mountains, Czech Republic (part 1; part 2). Here, I take a crack at brief narratives for four key parts of the story—trees, water, soil, and landforms. All the accompanying illustrations are from Mores—closeups are detail from his Biogeomorphological Domination piece, shown and analyzed in parts 1 and 2. Others are from preparatory work Petr did for that piece, and other examples of his paintings and drawings in the forests of the Czech Republic.

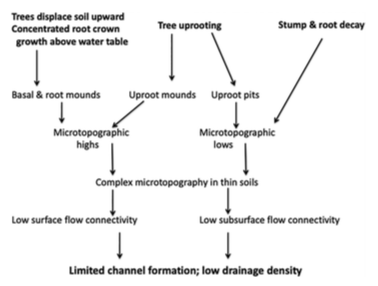

Tree story (general time scale: decades)