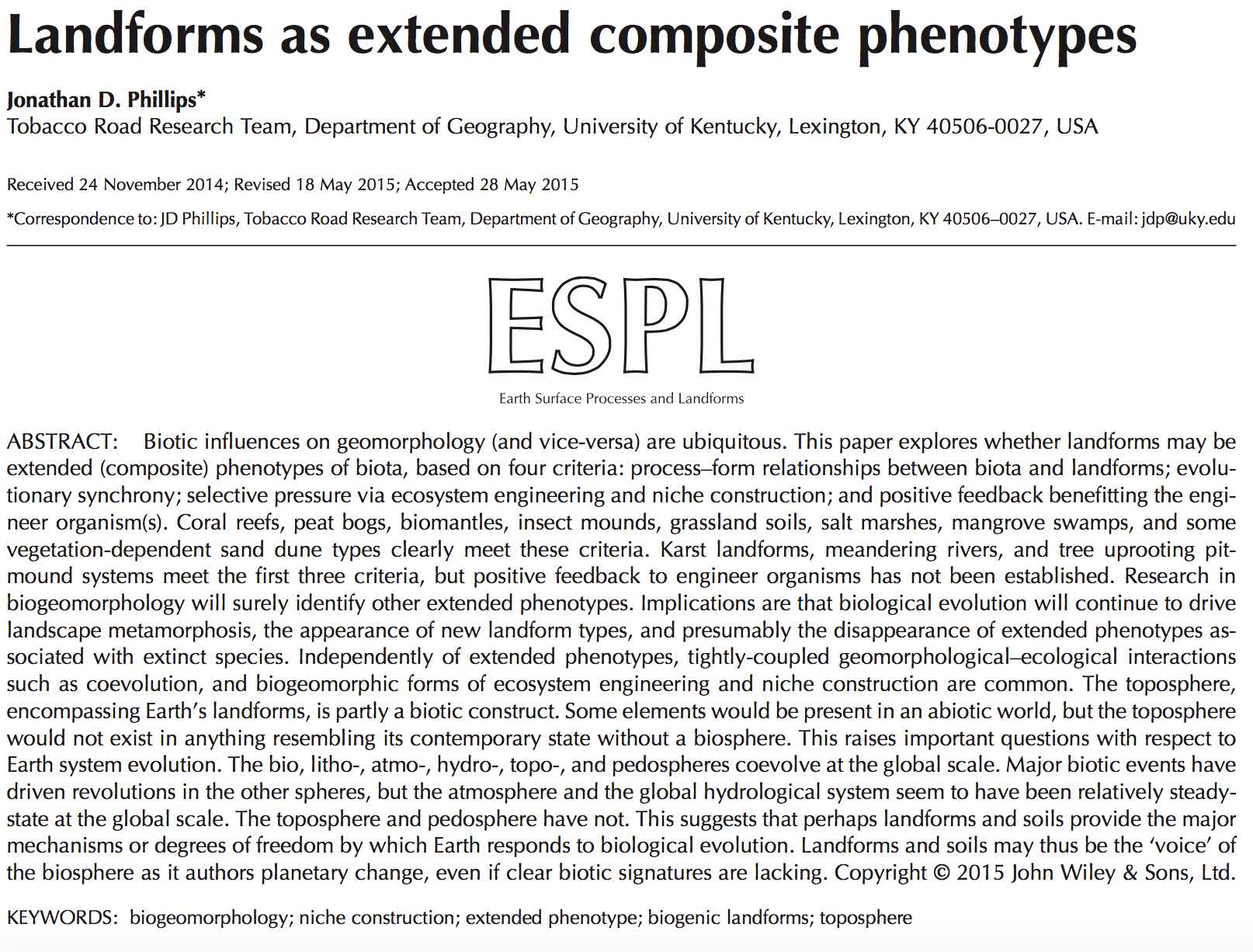

Landforms as Extended Composite Phenotypes

The online version of my new article exploring biogeomorphology from the perspective of niche construction and extended phenotypes is now out. The abstract is below. I appreciate my colleague Daehyun Kim encouraging me to stick with some of the more speculative and provocative ideas here. I was about to back off from them at one point, but he encouraged me to go for it.

Reference: Phillips, J.D. 2015. Landforms as extended compositive phenotypes. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms DOI: 10.1002/esp.3764.

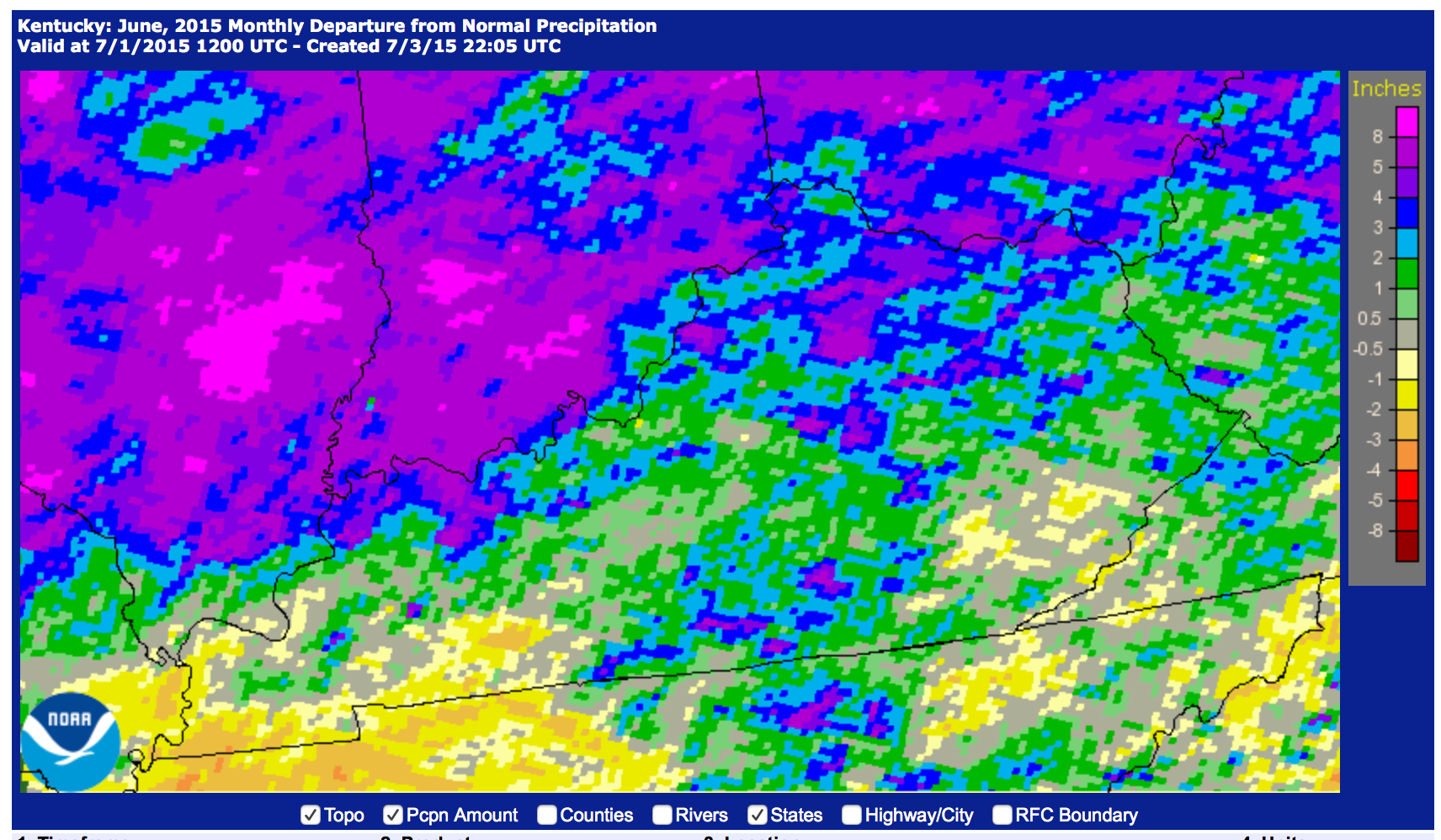

No, not like this.

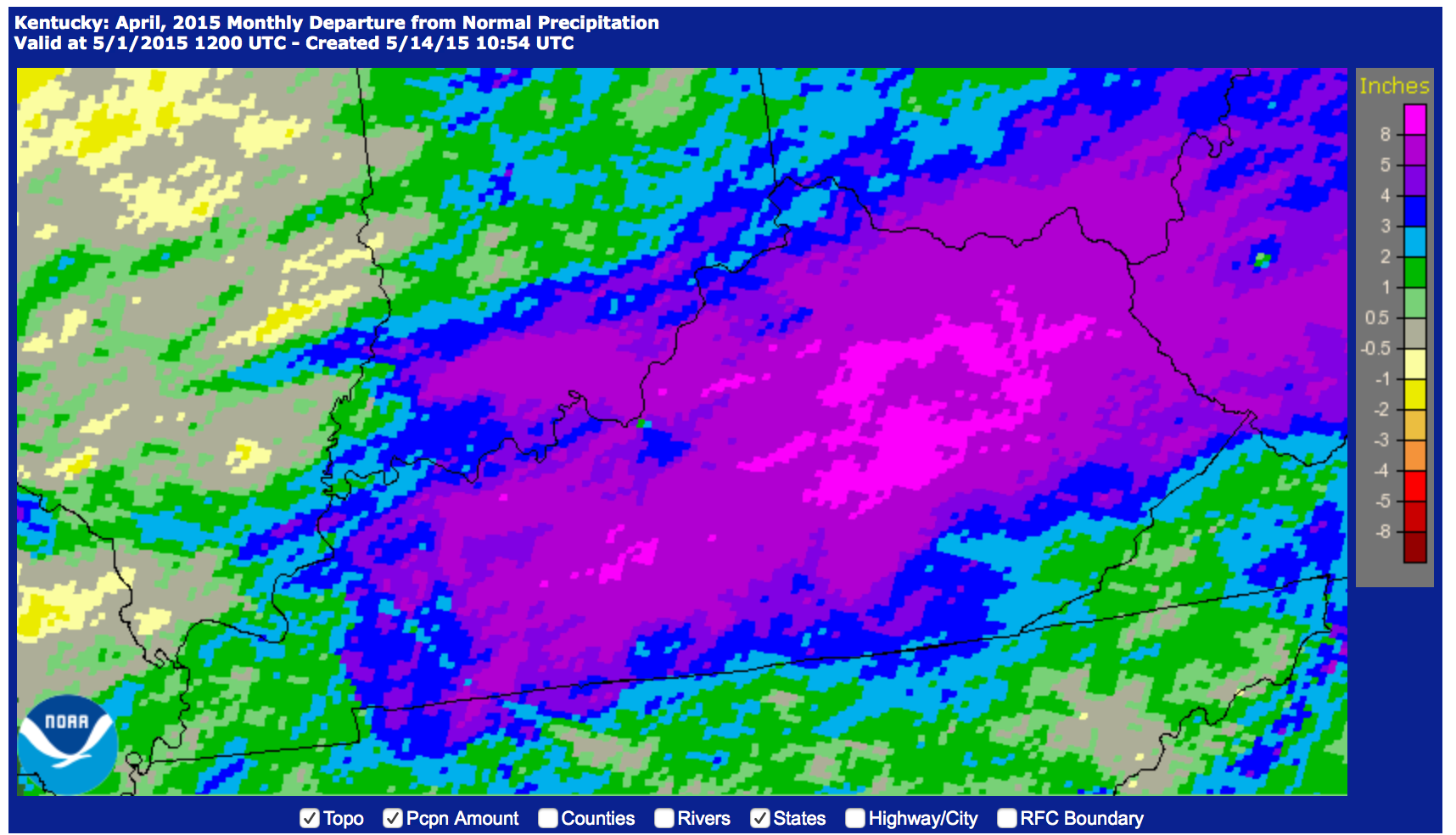

No, not like this.