In common parlance, romantic typically refers to the pursuit of love and affection, or to an idealistic, unrealistic outlook. The definitions of romantic as idealistic often includes synonyms such as dreamy, starry-eyed, impractical, and Quixotic, and may list realistic as an antonym. However, Romanticism (typically indicated with the capital R to distinguish it from other usages) as a movement of the late 18th and early 19th century applied to science as well as to art and literature. Lately I’ve stumbled across a few things that made me want to play with the idea of what a Romantic geomorphologist would be like.

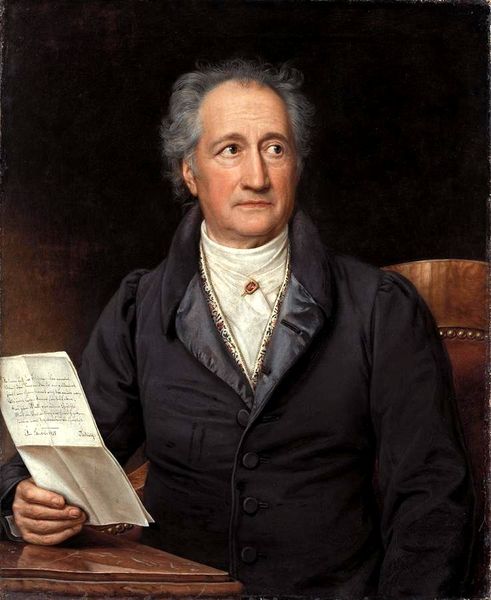

One was Daniel Gade’s book, Curiosity, Inquiry, and the Geographical Imagination (Peter Lang publishers, 2011). Among many other things, he draws a direct link between Romanticism and curiosity-driven inquiry, and proposed 14 tenets of the Romantic imagination as it relates to research. While focused on Gade’s specialty, cultural and historical geography, many of the tenets describe characteristics of the geoscience and geoscientists I most admire. A little further investigation indicated that some historical scientific giants I admire—Humboldt, Darwin, Gauss—are linked with the Romantic tradition, as well as some whose contributions span science and the creative arts (e.g., Goethe).

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832). Best known for his poetry & plays, he thought his scientific work would be recognized as his greatest contributions. This included work in geology, meteorology, & fluid dynamics.

According to Cunningham and Jardine’s introduction to their edited volume on Romanticism and the Sciences (Cambridge U.P., 1990), Romanticism in arts and literature had four basic principles: original unity of humans and nature in a “golden age”; later separation of humans from nature and the fragmentation of human faculties; interpretability of the universe in human, spiritual terms; and the possibility of salvation through the contemplation of nature. OK, this is not much of a blueprint for geomorphology or other sciences, but as a general background attitude for science, Romanticism promoted several themes that are relevant: Holism (admittedly in the form of anti-reductionism rather than in addition to reductionism), a sense of human-nature connection and recursive influences, and a valorization of creativity and experience. It began to seem as though there was some overlap with my notion of Badass Geomorphology.

Two of the tenets seem to apply more to the individual Romantic in than their approach to science and scholarship: an individualistic approach to research, and opposition to “officialism” (bureaucrasies and the status quo). These are right in line with my Badass Geomorphology archetype. So is the notion of historical perspective (“historicist vision”). While this certainly does not characterize all geoscientists, history is an important and irreducible part of our overall program.

Gade’s tenets of “interest in landscape form and content,” “affinity for the organic” (i.e., attention to self-organized wholes rather than parts), and “idea of process” (i.e., ongoing change), described in terms meant to contrast the Romantic with other approaches to cultural geography, are easily translatable to much geomorphological work. The scholar imbued with the Romantic imagination also unapologetically “stands on the shoulders” of previous observers, though this seems to me a hallmark of good scholarship from any perspective.

Romantics also reject utilitarianism. This does not mean they are unconcerned with the implications of their work for society or the planet, or that they reject pragmatism with respect to methods and techniques employed in research. It means that inquiry is driven strictly, or at least primarily, by a need or desire to know. The practical problem-solving value is secondary, and need not be apparent at the outset. I believe this characterizes many of us when we are first drawn to geomorphology, though the exigencies of thesis and dissertation proposals; research funding; and demonstrating “relevance” to governing boards and administrators often beats it out of us over time.

Five other tenets, termed by Gade as a search for the exotic, focus on particulars, depreciation of the obvious, a quest for authenticity, and diversity for its own sake, are a bit harder to reconcile with geomorphology. I’ll take these up in a future post.