No, not like this.

No, not like this.

Dang, it’s been raining a lot lately. Today, for instance, here in Mercer County, Kentucky, Herrington Lake’s level has risen almost 2 m in the last two weeks. Discharge of the Dix River has topped 1000 cfs (28.3 cms) twice in the past week, where the mean flow for early July is about 40 cfs (1.1 cms) over the past 71 years. We had another gully-washer, frog-choker rainstorm this morning.

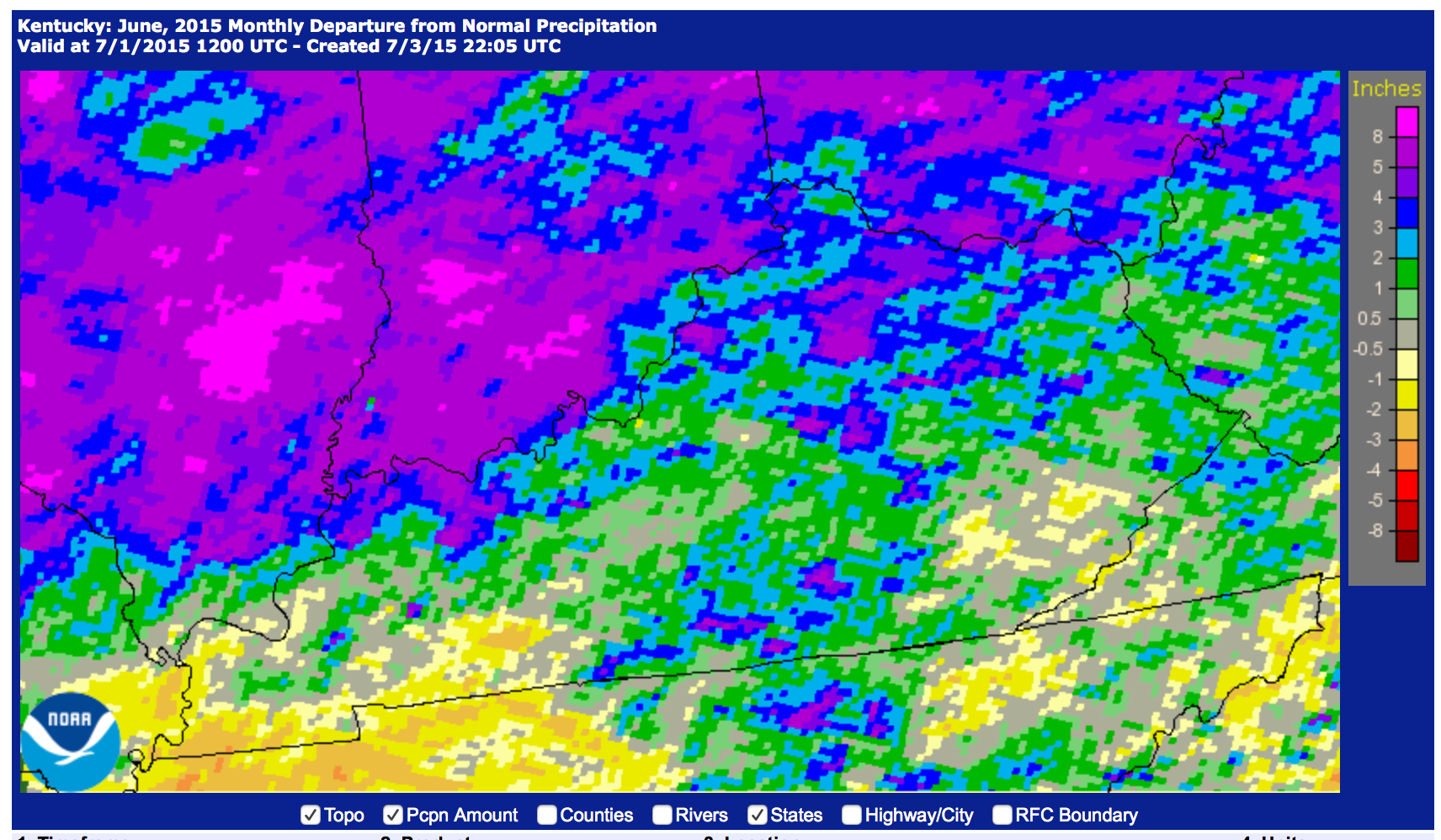

If it seems to have been an unusually wet summer here in Kentucky, you’re right. The graphic below shows departures from normal (mean) rainfall totals for June. That pinkish blob in north-central Kentucky, showing 8 inches (203 mm) above normal is the Lexington area.

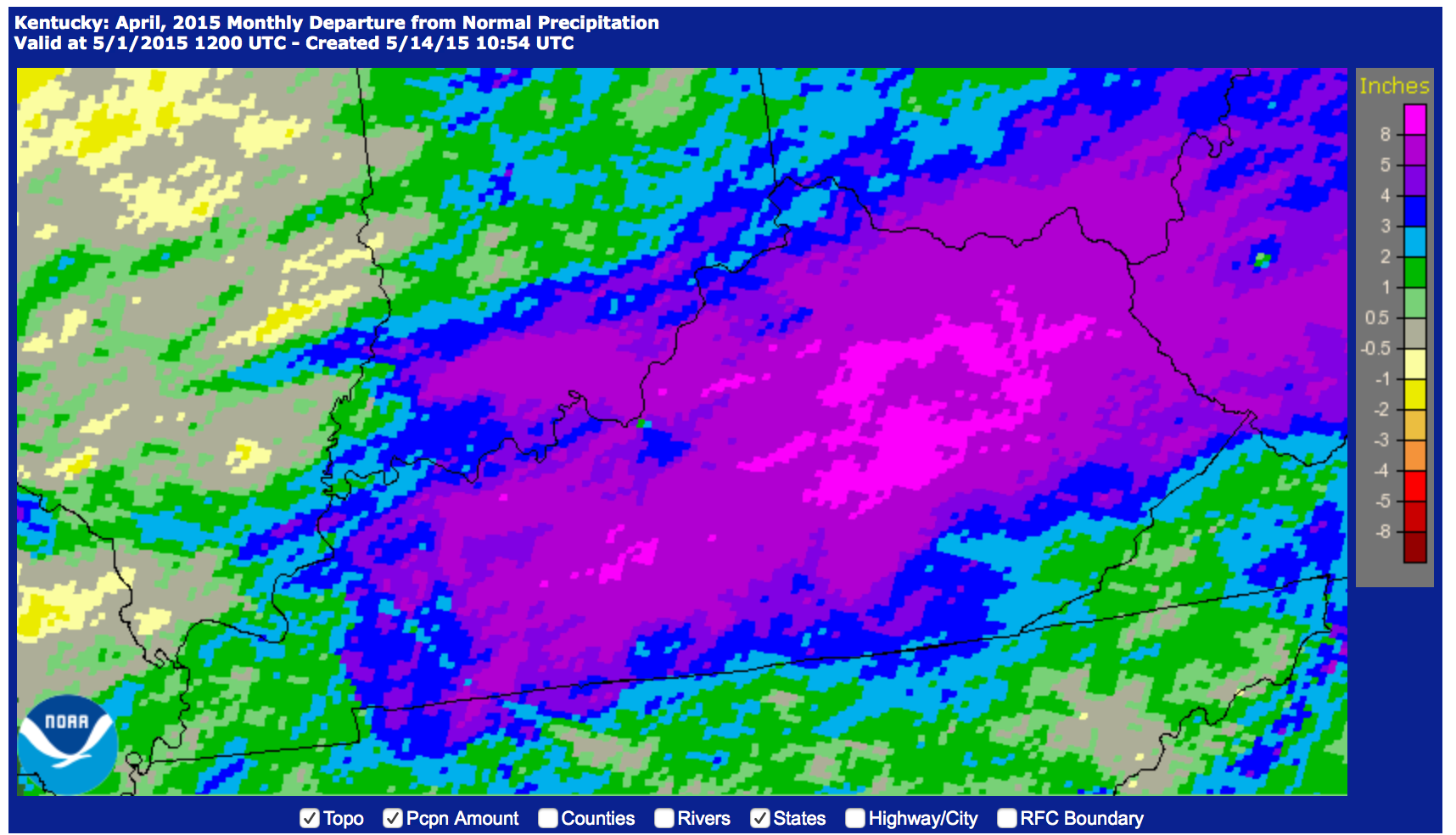

This follows a wet spring hereabouts. Below is the departure-from-normal precipitation map for April, 2015, a month in which one-day precipitation records were set in Lexington, Frankfort, and Louisville.

So is there a point, other than griping about a wet spring and summer?

Some recently-published work confirms some earlier studies in showing that ongoing global warming results in more heavy precipitation events. In this case, a team from Germany’s Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) looked specifically at record-breaking rainfall events. According to a PIK summary: “Heavy rainfall events setting ever new records have been increasing strikingly in the past thirty years. While before 1980, multi-decadal fluctuations in extreme rainfall events are explained by natural variability, a team of scientists detected a clear upward trend in the past few decades towards more unprecedented daily rainfall events . . . An advanced statistical analysis of rainfall data from the years 1901 to 2010 derived from thousands of weather stations around the globe shows that over 1980-2010 there were 12 percent more of these events than expected in a stationary climate, a scenario without global warming.”

Climatologists have long suspected, and then known, that a warmer climate accelerates the hydrological cycle. Evaporation and transpiration go faster at higher temperatures, recycling water vapor into the atmosphere faster, where it is eventually returned as precipitation. Warmer air can hold more water vapor, and vapor-laden air masses are a key in developing intense precipitation events.

The latest downpour here in Mercer County, or the big rainfalls of April, like any individual meteorological event or episode, are neither proof nor refutation of a climate trend (in the June map above, for instance, you can see parts of Kentucky that had below average rainfall). But it seems clear that from here on out we can expect more frequent and intense heavy rainfall events, and more days like today1 (another thunderstorm rain just started outside). That means more runoff (other things being equal, the faster rain falls, the greater the proportion of surface runoff), more soil erosion, and more floods.

So this is about much more than my dog tracking mud all over the house. We should be on the lookout for possible related changes in dominant runoff mechanisms, flood frequencies, soil erosion rates, and nonpoint source water pollution.

The reference for the PIK study is below; the press release is here.

Jascha Lehmann, Dim Coumou, Katja Frieler. Increased record-breaking precipitation eventsunder global warming. Climatic Change, 2015; DOI: 10.1007/s10584-015-1434-y

1July 12, 2015. Not sure when I’ll get this posted, since these torrential downpours interreupt my satellite-based internet.