Where forests grow on thin soils over bedrock, the effects of individual trees (as well as the effects of forest cover and litter) may work to deepen or thicken the soil. This occurs due to root penetration of bedrock joints and fractures. This in turn facilitates weathering and funnels moisture into the rock. Uprooting of trees may “mine” bedrock encircled by roots, and leave a locally thicker mound as rootwads deteriorate. If trees do not uproot, as stumps rot away the depressions—often extending deeper than surrounding soil—fill with soil, sediment, and organic matter. This thickening of the soil is a form of direct, positive ecosystem engineering in that it increases habitat suitability for the engineer organisms (the trees).

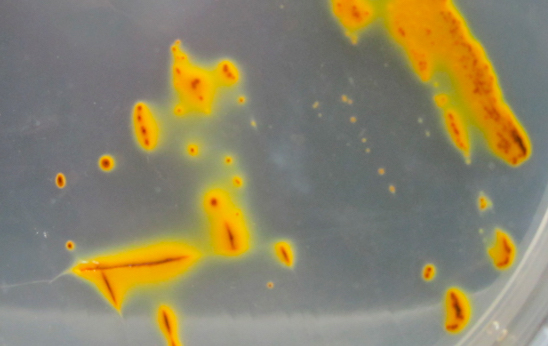

Chinquapin Oak growing in limestone, Mercer County, Kentucky.

Eventually, however, the average soil or regolith thickness may increase such that tree roots no longer contact bedrock. Then the biogeomorphic ecosystem engineering effects of the trees on soil thickness ceases. In effect, you have self-limited biogeomorphic ecosystem engineering.