Strat-and-Transition Models II

This is a continuation of my earlier post on applying state-and-transition models (STM) to stratigraphic information, to account for the missing bits.

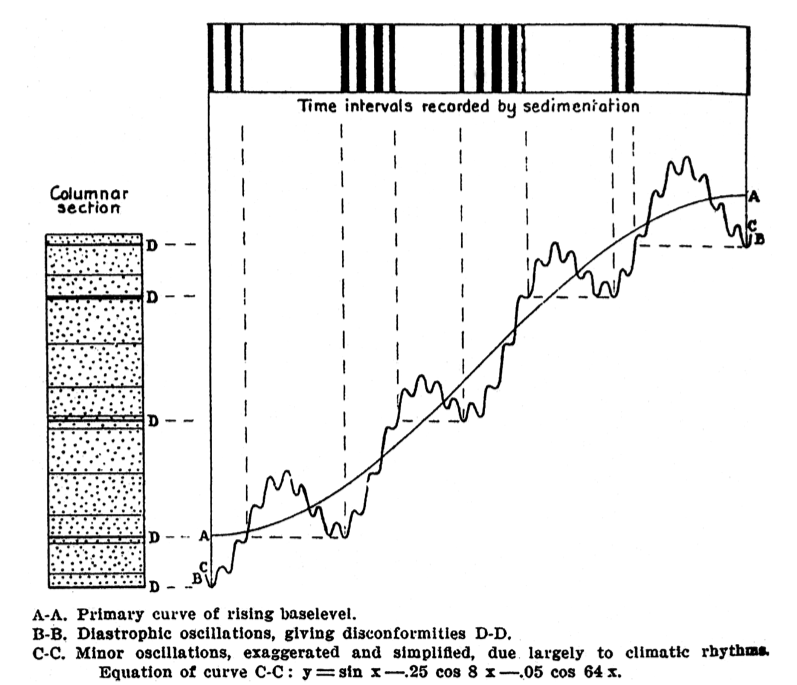

Barrell’s (1917) explanation of how oscillatory variations in base level control the timing of deposition. Sedimentation can only occur when base level is actively rising. These short intervals are indicated by the black bars in the top diagram. The resulting stratigraphic column, shown at the left, is full of disconformities, but appears to be the result of continuous sedimentation. Noted sedimentologist Andrew Miall has used this example in several articles to illustrate the problems of gaps in sedimentary & stratigraphic records.