My approach to the study of the structure, function, and evolution of Earth surface systems (landscapes) is based on the premise that they are controlled and influenced by three sets of factors, summarized as laws, place, and history. Law represents laws per se, such as the conservation of mass, energy, and momentum, and also for other generalizations and representations that are independent of location and time. Place represents the environmental context in which laws operate – ‘other things’ that are rarely equal. Path-dependent, historically contingent aspects of landscapes comprise the history. These may include sensitivity to initial conditions, previous evolutionary or developmental pathways, stages of development, disturbance histories, and time available for system development or evolution.

My work and my approach also emphasize multiple possible evolutionary pathways and outcomes, the sensitivity of many Earth surface systems to seemingly minor variations and disturbances, and the amazing variety of landscapes resulting therefrom. These are discussed in fascinating/excruciating detail in my to-be-published-any-day-now book, Landscape Evolution.

Though the book might be the last thing I ever publish on the subject, I continue to think about it. While marveling at how Albert Collins, Roy Buchanan, Merle Haggard, Waylon Jennings, Danny Gatton, Muddy Waters, Bruce Springsteen, and Pete Townsend (among many others) could get such wonderful and different sounds from the same model of the same instrument, a Fender Telecaster electric guitar, it occurred to me that musical instruments are a fitting metaphor for landscapes.

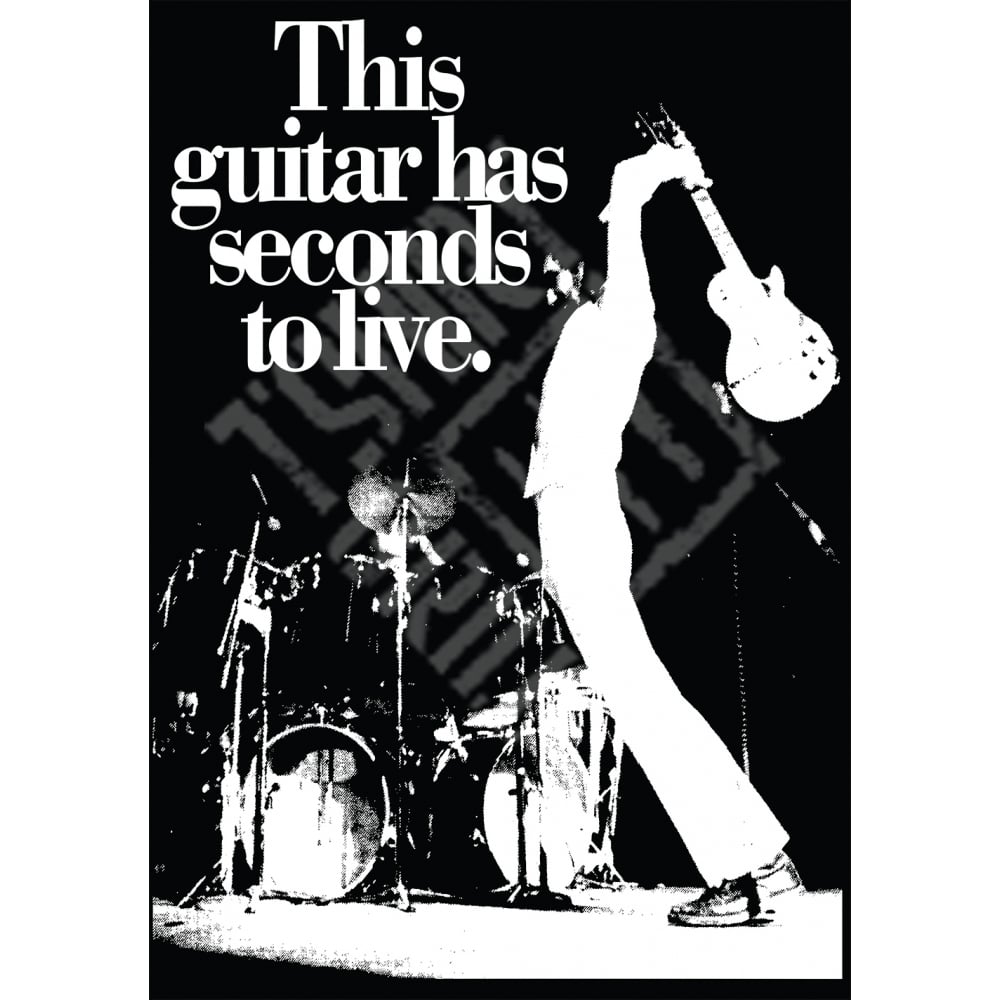

Early-career Pete Townsend of The Who about to smash a Telecaster. Though such smashing was his trademark in the 1960s, he reportedly spared his favorite, a 1952 Telecaster.

Bear with me on this.

The range of sounds that can be emitted or coaxed from any given musical instrument, be it an alto saxophone, grand piano, Hammond B-3 organ or whatever, is finite and limited by fundamentals of physics and acoustics. This is directly analogous to the laws governing landscape evolution.

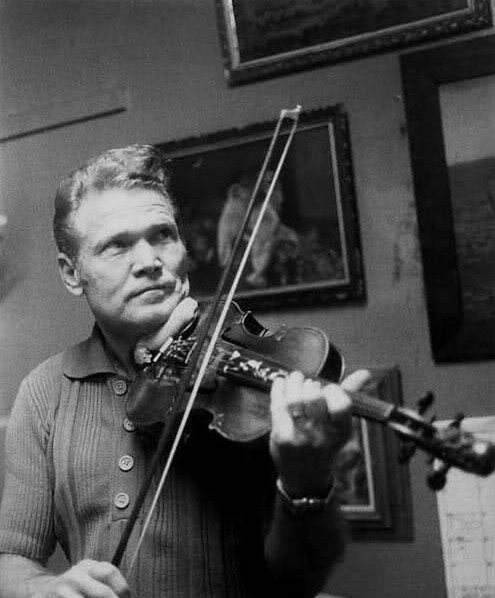

These possible sounds are constrained by specific properties of the individual instrument. A Stradivarius violin presents different possibilities than the Duiffoprugcar played by legendary fiddler Vassar Clements (yeah, I just looked that up; I don’t really know much about violins) or the cheap elementary school orchestra model. The B-3 famously has a sound different even from other Hammond organs, and so on. There are also, of course, individual modifications. Electric guitarists use a variety of custom pickups (whatever those are), and of course they can be tuned differently. Bo Diddley built his style around an open-E, which has come to be called the Bo Diddley tuning. These features of individual instruments are comparable to the place factors in Earth surface systems.

Vassar Clements and his fiddle, believed to date from the 15th century. It was given to him by John Hartford.

Though there are a finite (even if very large) number of sounds that can be obtained from a given instrument, there are an infinite number of potential sequences of notes or other sounds. This is the history factor.

How many different songs are there? How many different songs could there be? And keep in mind that the same song is not always the same song. Each season of the TV show The Wire, for instance, had a different version of the Tom Waits composition Down in the Hole as the theme music.

Comparably, we could ask how many different landscapes or landscape evolutionary trajectories exist, have existed, or could exist. The possibilities are endless.

Of course, not every landscape song is a John Coltrane or an Allman Brothers improvisation, or even a new tune. Music can be formulaic, with certain patterns recurring because of their popularity, inherent attraction for the human ear, or suitability for a particular purpose. Baa-Baa Black Sheep; Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star; and the Alphabet Song all have the same tune (based on a French children’s song) because it is pleasing to the young ear and easy for small children to sing. Many country trucking songs have a similar syncopated rhythm because it gives a feel of the highway. Likewise, in landscapes patterns and structures recur mainly because they are selected for in some way (efficiency selection is another major theme in my forthcoming book).

Rahsaan Roland Kirk (1935-1977), an astounding improvisational jazz musician who could play several instruments simultaneously, at a virtuoso level. I leave the reader to ponder the landscape evolution analog of this.

Anyway, if you want to think of landscape evolution the way that I do (and to be sure, a lot of scientists do not want to), the metaphor of landscape songs is not a bad way to start.

-------------------------------------------------------------------

Posted 28 April 2021