As climate change and its many impacts unfold, many worse than we had forecasted or feared, many observers have indicated that Earth is entering a “new normal.” This is not wrong. However, with respect to our ability to understand, adapt to, and predict environmental change from here on out, it is probably more accurate to say there is no normal. The climate and environment that we will contend with will be unlike any our species—much less our infrastructures, institutions, and cultures—has ever encountered. I agree with those who say, sometimes circumspectly and sometimes directly, that it is time to panic. Not in the sense of panic as uncontrollable fear or anxiety that can cause wildly unthinking behavior, but in the sense of another definition: a frenzied hurry to do something. Scientists hate to be called alarmist, but when the house is on fire, you sound the alarm.

New York Times, February, 2019

Do something involves taking whatever measures we can, as vigorously and as soon as we can, to cut anthropic carbon emissions and limit the damage. Do something involves recognizing that a change is underway, like it or not. To ask whether one believes in climate change is like asking whether they believe in cells or earthquakes—climate change, cells and earthquakes exist, whether you or I believe them or not. Do something involves figuring out how to adapt to change and mitigate its adverse impacts.

There are more thoughtful and knowledgeable folks to elaborate on the points above. I’ve been trying to think about how geoscientists and environmental scientists can best do something in our professional lives. For those directly involved in climate science this is probably evident. For the rest of us, even those who have not been involved in studying climate change impacts have to come to grips that climate change is influencing, or soon will, everything we study—landforms, soils, ecosystems, water resources, and on and on. That doesn’t necessarily mean that every geomorphologist, hydrologist, or ecologist should make climate impacts the focus of their work. It does mean that we should think about how what we know, think we know, and learn can inform our understanding of and adaptations to climate change and its impacts.

Because Everything is Connected to Everything Else (the first law of geography) and All Other Things are Never Equal (2nd law of geography) we will have to confront more complexity. The first and second laws have always applied, but global climate shifts change everything, at more or less the same time. Experience will be less helpful as we move into unchartered territory.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832) had it right.

I need to think more about this. We all need to think more about this. But I do have two recommendations to start with.

From precedents to analogs

Much can be, has been, and will be learned from studying the closest precedents we can find in Earth history to the current and near-future situation—periods of higher or rising temperatures, greater carbon dioxide emissions, rising sea-levels, etc. But with respect to effects on human affairs, we are quickly encountering situations and scenarios for which there are no precedents. And even though there were episodes of, e.g., rising sea level or retreating glaciers in the past, those rising seas did not threaten developed coastlines and those glaciers were not water supplies for human settlements.

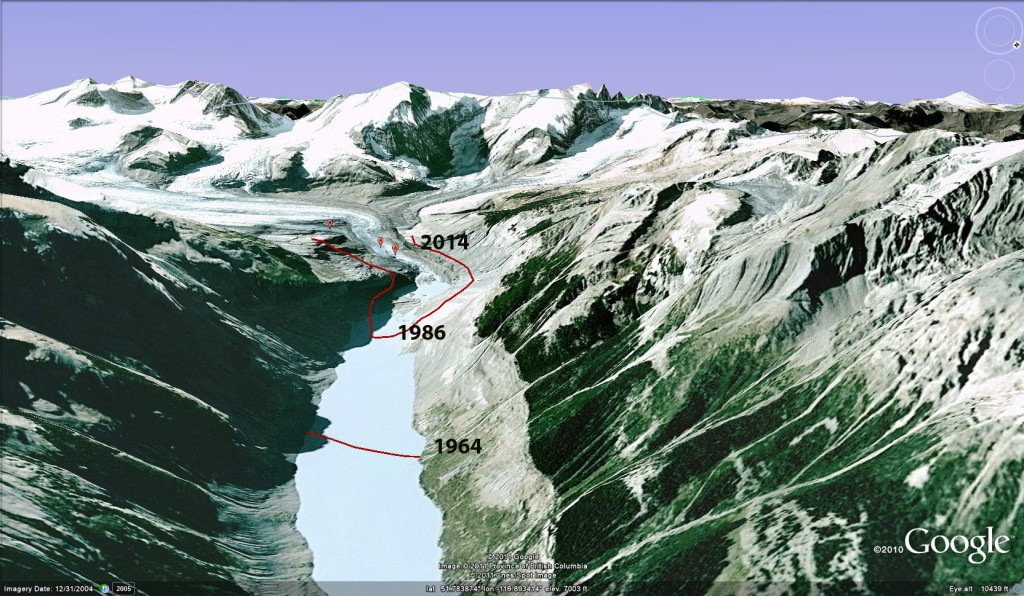

In addition to examining precedents, we should be looking for analogs. In many cases these will be hotspots of recent and contemporary change that may be bellwethers for more general or global phenomena. For instance, lessons from places such as south Louisiana, where subsidence and other factors create a rate of relative sea level rise greater than the rate of eustatic sea level change, may be crucial in an era of accelerating global sea level rise. Rather than focusing on typical or average glaciers, studies of those retreating most rapidly may provide the most useful information for assessing future impacts of glacial decline.

Freshfield Glacier, Alberta, Canada showing 1964, 1986 and 2014 terminus positions (Mauri Pelto, American Geophysical Union).

This may sometimes go against our training and traditions—after all, most of us were taught and conditioned to seek a holy grail of “representative” sites. We need to shift (or at least broaden) that focus from seeking out sites representative of what was going on until recently, to locations representative of the overheated, rapidly changing world we find ourselves in.

From trajectories to trails

We often speak of past and future in terms of historical trajectories. The formal definition has to do with the path following by an object moving under the action of given forces. The paths and velocities may be inconstant, and trajectories can be modified, but the implication that they are deterministic and covered by (presumably known) rules is entirely consistent with the way Earth and environmental scientists typically think of historical trajectories.

Trails may be a better metaphor for ongoing and future change. While the rules or laws governing development of Earth systems may be constant, the boundary conditions and inputs are shifting rapidly. And the historically and geographically independent rules and laws are not the only thing influencing evolutionary pathways. Trails are influenced and partly constrained by invariant principles, but also by idiosyncratic, historically contingent controls, and potentially affected by a variety of factors that have little or nothing to do with the physics of movement. This, I think, is a better metaphor for the interpretive and predictive problems we face, particularly if (or as) critical thresholds (e.g., a sea ice-free arctic summer; ocean heat absorption; livability of overheated cities) are crossed.

Posted 19 February 2019