In the brief biography on my departmental web page, I refer to myself as the "author of a vast number of widely-ignored articles." This statement reflects the lifelong tug-of-war between my inherent boastful, egotistical leanings and the humility my parents tried, with mixed success, to instill. Thus the boastful "vast number" juxtaposed with the humble "widely ignored." The latter, by the way, is based on the relatively low number of citations and other metrics generated by ISI, etc., compared to the most popular and influential scholars.

I revisit this because I got an e-mail from a master's student working on a research paper who asked: "When going through the bio section of the webpage for the university you work for, it says that a lot of your work is widely ignored. I am wondering why this is, as I have seen some of your work and think it is fascinating. Maybe you could help me in this matter by explaining a little further?" The egomaniac within wants to answer that it is because I am so far out front that few have caught up with me; a genius-ahead-of-his-time narrative. The answer dictated by my upbringing (which in this regard is typical for anyone of my generation raised in the small-town or rural USA) is that I just need to try harder and do better (and thanks for the compliment!).

But really, why do scientific publications get ignored, or not? I tried to think this through both in general and in my case.

First, of course, is the awful possibility that the work is simply crap. The conclusions or interpretations are wrong or unsupported; methods or data of poor quality; the results are unhelpful or uninteresting; the findings are old news; etc., etc. Though some of my work has flaws and errors, and some has certainly been improved upon, I can't bring myself to admit that any of it is simply too bad to be worth a read (though I have to acknowledge that possibility). As far as I know, no one has shown that the major findings of any of my papers is dead wrong (although maybe no one thought it important enough to try).

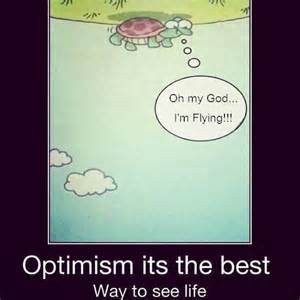

I hope my work isn't registering too far on the left of this meter.

Second, even if the science or scholarship is good, the presentation and communication can be so poor that its quality, value, or interest is unclear or invisible. Again, I can't bring myself to confess to this crime (I was a journalist in a brief earlier professional life), though some referees have disagreed. But there's no doubt I could do or have done better in this regard. I do try. For example, one paper that I think has some of my most interesting theoretical results just proved hard to write up. If I had figured out a way to communicate it more clearly, it might have gotten more than the 18 citations (2 by me) in 11 years that is has garnered.

Third, a solid, well-written paper may simply deal with an unpopular topic. The subject may be outdated, esoteric, or simply unfashionable. In the 1980s, for example, I did a bit of work on soil erosion modeling. One journal reviewer remarked that one of my papers was sound enough and useful enough, but that erosion assessment was so dominated by the U.S. Department of Agriculture's programs and paradigms that it was pointless to publish alternatives. Since my approach was geared toward on-the-ground practical applications rather than theory, why bother? The article was rejected, though I eventually put it into an obscure proceedings volume.

Which brings us to item four, obscure venues. Work can escape notice because it is published in things few people read. These can be regional journals of limited circulation, proceedings, technical reports and other "gray literature," and other outlets of limited circulation. I have indeed published three times in a regional journal (The Southeastern Geographer, which is actually a good-quality journal). I also had the misfortune of putting what I still think is a pretty good paper into Geographical and Environmental Modeling. Never heard of it? That's because it lasted only six years, and my paper was in its very last issue in 2002.

This does not apply to yours truly, but increasingly "obscure" can mean non-English. Most international scientific literature is now published in English, so even excellent highly relevant work published in prestigious outlets in another language can get ignored.

Fifth, I should note that poorly cited does not necessarily mean ignored. Some work (e.g., "thought pieces," reflections on scientific trends and practice, etc.) may be widely read and assigned in graduate seminars without being cited. Also, some applied or technical/methodological research may be used or applied in practice without being cited much in the literature.

Here I am not being ignored, by some of my beloved students who brought me a gift basket (containing two of my favorite things, Kentucky bourbon, and chocolate) following my recent heart surgery.

Sixth, maybe politics plays a role. I have no reason to believe that any of my work has ever been given short shrift due to any of my scientific connections or allegiances, or my methodological affinities. However, I firmly believe that this has happened to some geoscientists whose work deserves better. And I know damn well it happens in social sciences and humanities, where politics are (unavoidably) more prevalent. I have even heard rumors of "citation circles"--scholars who agree to cite each other's work. Certainly sociology and politics can play a positive role--being wired in with an "invisible college" can ensure your publications get noticed, and increase the likelihood of citation. This is sometimes absolutely innocent--it is simply human nature that you are more likely to pay attention to work by people you know.

Seventh, and finally, there is (at least I fervently hope, in my case) always the possibility that the work is ignored because it is indeed ahead of its time; so advanced and/or innovative that few are prepared to deal with it. One can always hope . . . .

Image: http://www.devinchughes.com